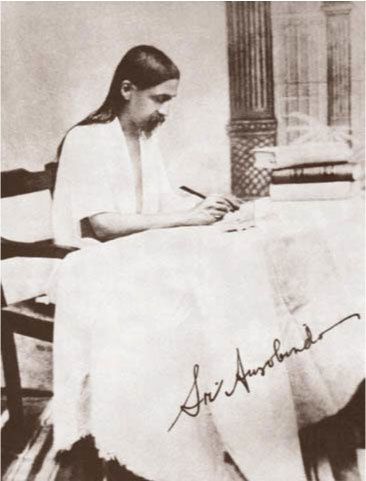

Sri Aurobindo

We thank Prof. Giuseppe Cognetti for having granted the precious contributions relating to the work and personality of Sri Aurobindo.

The fragments are taken from an intervention given by the teacher on the occasion of an academic meeting dedicated to Sri Aurobindo held at the Siena Faculty on July 9, 2005.

Sri Aurobindo’s works abroad enjoy a lot of fame and are also read by “non-experts”. In Italy the name of this illuminating author resonates in the places where yoga is practiced and remains somewhat confined to academic studies. A real shame, because reading and knowing Sri Aurobindo is an experience in the true sense of the word, a passing through something that can change us, for the better, that is, in the sense of openness to others and to oneself.

Sri Aurobindo (Calcutta 1872 – Pondichéry 1950)

It could be said that Sri Aurobindo was a philosopher, but the term should not be associated with a dimension of pure thought. Sri Aurobindo was a philosopher who maintained constant contact with “the craft of living”; a thinker who has “dirty” himself with life, without relegating everyday life to something foreign or inferior to philosophical speculations. Because in India a philosopher is also a teacher of life. And viceversa.

Sri Aurobindo, a life steeped in spiritual research

Sri Aurobindo was born into a wealthy Bengali family and studied at the University of Cambridge, England, where he remained for 14 years. He was able to enter Cambirdge thanks to a scholarship in classical literature awarded to him by St. Paul’s School in London. In 1893 he returned to India, joined the nationalist movement and at the age of 29 he married a woman who would not have accompanied him or followed him along his path of acquaintance.

From Calcutta he wrote his editorials (he wrote for the Bande Mataram newspaper ) which quickly became the inspired voice of the nationalist party, a voice that pushed men and women to think of a possible independence, to be achieved through a form of resistance. passive aimed at subverting the foundations of the British government in India. He was arrested and imprisoned in 1907, on suspicion of involvement in a bomb-making affair.

In prison there was the turning point. It is in captivity, in fact, that the philosopher’s thought was freed, heading towards contemplation. He received an inner order in the form of intuition, a simple and powerful command that materialized in his mind: “Go to Pondichéry”. Embarking on a false name aboard the Dupleix, he arrived in Pondichéry on April 4, 1910 and retired to an ashram (hermitage), which became the fertile ground on which Sri Aurobindo lays the foundations of his integral yoga , surrounded by disciples united in one solid and united community.

In 1914 he met Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa for the first time, the future Mother , who had come to Pondichéry with her husband, the French philosopher Paul Richard. The latter convinces Sri Aurobindo to explain his thoughts and vision of him in writing. Thus were born, from 1914 to 1920, almost all the great works of Sri Aurobindo, including: Divine Life , Synthesis of Yoga , Human Cycle , Ideal of Human Unity . When the First World War broke out, the Richards were forced to leave Pondichéry.

Mother will return, and this time forever, next to Sri Aurobindo in April 1920. In 1926 Sri Aurobindo definitively retired to his rooms, leaving the management of the ashram and contact with the disciples entirely in the hands of the Mother. Sri Aurobindo left his physical body on December 5, 1950. The vision of Sri Aurobindo and Mother is kept alive in the seaside town of Auroville , 10km north of Pondicherry and 160km south of Madras. Founded in 1968 on a project by Mère, it is unique in the world.

You can learn more about the benefits and techniques of Aurobindian meditation

Sri Aurobindo’s integral yoga: philosophy close to life

Sri Aurobindo’s spiritualistic-evolutionary philosophy was widespread and successful even outside India, thanks to Aurobindo’s numerous writings made up of words that exude life and reach right into the body and spirit of the reader. His texts reflect a syncretism of Eastern culture and some Western philosophies, such as those of FH Bradley and H. Bergson, whose thought influenced Aurobindo quite intensely.

Giuseppe Cognetti , Professor of Comparative Philosophy of Religions at the University of Siena with long experience in oriental body techniques, explains it in more exhaustive words: Sri Aurobindo also knew Italian culture: Dante, Mazzini; he also dealt with the issue of the Risorgimento, since he was very interested in active politics. He therefore acquired the hermeneutical and philosophical categories of the culture of the second half of the 19th century, which are well present in certain features of his philosophy.

According to Aurobindo, man’s vocation consists in achieving communion with the divine power that acts in the cosmos, the shakti (from the Sanskrit “power, strength”, appellative of Parvati-Kali, wife of Shiva), through an induced transformation of consciousness from its integral yoga ( purna-yoga ), which, unlike traditional yoga, seeks to integrate the divine also into everyday life and material life.

Also by Prof. G. Cognetti the definition of Sri Aurobindo as “intercultural philosopher”, in the sense that the typical characteristic of the Aurobindian aspiration is to build bridges. That is, Sri Aurobindo is not a dogmatic philosopher. He is a thinker who has always tried to build unifying bridges, but without these bridges abolishing differences; in this sense he is a pioneer of interculturality, in the sense that he too believed that the Truth – even the one with a capital letter – is completely pluralistic and that it is therefore a matter of building bridges, that is, of dialogue not in a dialectical sense, but in a dialogical * and existential, and above all not to stop at certain unilateral visions of the world.

* The difference refers to the distance that the great philosopher Raimon Panikkar places between dialogical dialogue and dialectical dialogue, between optimism of reason and optimism of the heart. Panikkar speaks of dialogic dialogue rather than dialectical dialogue, or rather enriches the traditional scheme of the dialectic of Hegelian and Marxian imprint, of a new figure capable of understanding the interlocutor in its entirety, without the passage from the antithesis and then merging into the synthesis.

In this sense, dialogue is a religious act par excellence, as it recognizes my religatio to another, my individual poverty, the need to get out of myself, to transcend myself in order to be able to save myself.

(R. Panikkar, Myth, Faith and Hermeneutics, translation from English by Silvia Costantino, Italian edition edited by Milena Carrara Pavan, Jaca Book, Milan, 2000, p.243)

+ There are no comments

Add yours